Does the name Carl Lutz mean anything to you? Probably not. That’s because his remarkable story of heroism during the Second World War had been largely forgotten – until now.

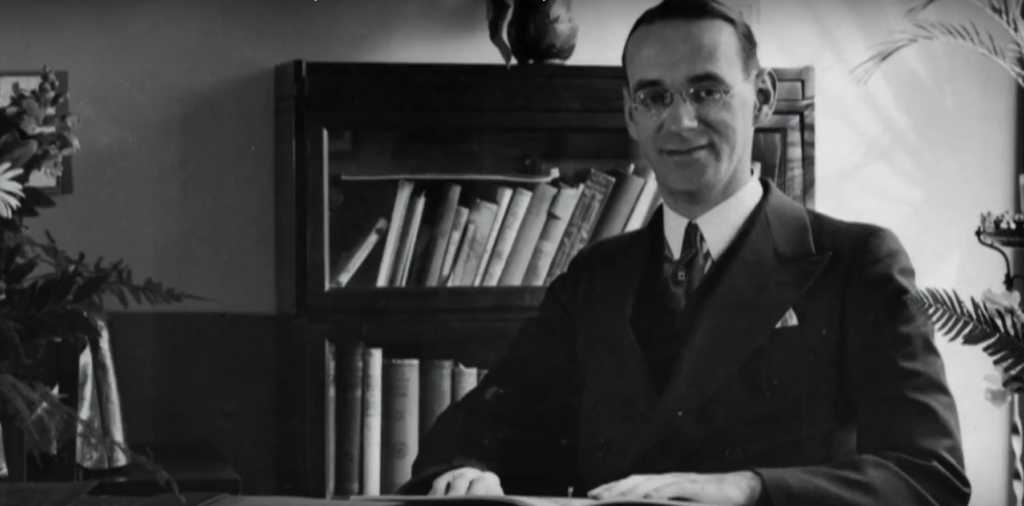

nAn experienced diplomat, Mr. Lutz had served as the Swiss consul to Palestine, then under British mandate, in the 1930s. His extraordinarily risky actions to save thousands of Jews from the gas chambers have earned him the name “Switzerland’s Schindler.”

Lutz was sent to Budapest in 1942. A year earlier, Hungary had joined the war on the German side and the Nazis were just gearing up to occupy the nation. The rooting out and deportation of Hungary’s vast Jewish population was almost immediate.

“After the German occupation of Budapest, the Hungarian Jewry in the countryside was in very quick succession deported to Auschwitz,” said Holocaust expert Charlotte Schallié, as reported by the BBC.

“Lutz realized he needed to act very quickly.”

With a bit of ingenuity, and utilizing his credentials a diplomat, Lutz managed to engineer the rescue of thousands.

In his official capacity as an envoy for Switzerland, Lutz represented the interests of those nations who had closed their embassies in Hungary, including Britain and the United States. So, he began placing under Swiss protection anyone connected to the countries he represented.

Agnes Hirschi was just one of his many beneficiaries. She was born in the UK to Hungarian parents who returned home to Budapest. “My mother and I went to the Swiss consulate,” she told the BBC. “We were all dressed up. Carl Lutz was there at a big desk. And he gave me a protective passport.”

But Lutz realized this was not going to be enough. In an astonishingly bold move, he managed to convince the Nazis to allow him to issue some 8,000 diplomatic letters of protection.

The Nazi authorities were acting on the understanding that one letter would grant just a single individual diplomatic protection, but Lutz had other ideas. He issued them per family, covering thousands with an umbrella of protection against the German’s murderous regime.

He did not stop at 8,000 families, however. Once he reached his 7,999th letter, he simply repeated the process and hoped that the Nazis wouldn’t notice anything was awry.

Historians estimate that his letters saved up to 62,000 people.

“It is the largest civilian rescue operation of the Second World War,” said Charlotte Schallié.

Fellow diplomats got word of Lutz’ actions and followed suit. Eventually, the Nazis caught on to his protection scheme and many officials called for him to be assassinated, though this never came to pass.

As it became clear that winning the war was beyond the grasp of Hitler’s German forces, the Nazis grew ever more brutal in their slaying of the Jewish community in Hungary.

With little time for the organization of deportations, SS troops rounded up Jewish families, marched them to the banks of the river Danube, and shot them dead. Lutz once again stepped in to try and stem the bloodshed and save lives.

On one occasion, the courageous diplomat dived into the Danube River to save a bleeding Jewish woman after fascist militiamen opened fire.

Keeping her afloat, Lutz dragged the injured woman back to the river bank and demanded to speak to the officer in charge of the firing squad. Quoting international treaties, he began to speak with authority to the commanding officer, convincing him that the woman was a foreign national under Swiss diplomatic protection.

Lutz marched the injured woman back to his car in front of the stunned militants. Incredibly, no one dared question him.

The quay where this took place in Budapest now bears his name: Carl Lutz Rakpart.

But Lutz wanted to find a way to save people en masse. So he set up 76 safe houses. Again, he was shrewd in his tactics. The properties were technically located in the relative safety of Switzerland’s territory, so the shelters took in thousands.

Among the safe houses was the now notorious “Glass House” (Üvegház) at Vadász Street 29. Approximately 3,000 Hungarian Jews found refuge at the Glass House and in a neighboring building.

Both Sweden and the Red Cross also set up safe houses too. In total, Budapest was home to some 120 safe houses, saving thousands upon thousands from certain death.

“I celebrated my seventh birthday in that cellar,” said Agnes Hirschi, who was once of those who evaded capture by taking refuge in safe house. She also recalled meeting Mr. Lutz in person.

“And Carl Lutz was a very nice man,” she said. “He had some chocolate for me, which he had saved.”

Lutz himself spent two whole months hiding from German forces in a basement cellar.

When the war eventually came to an end, Carl Lutz was ordered back to Switzerland, where he half expected a hero’s welcome. But there was none.

“The huge disappointment was that there was no-one,” he recalled in an interview shortly before his death in 1975. “I was just asked, ‘Do you have anything to declare?'”

Instead, he was reprimanded for overstepping the realms of his authority.

“No one thanked me, they just told me I was lucky to survive the war. No government minister even shook my hand.”

Despite his home nation’s unwavering commitment to neutrality and ardent refusal to recognize him as anything more than a rogue diplomat, Lutz was viewed as a man of astonishing bravery and honor by all of those he saved.

“I think he was a hero,” said Agnes, who later became Lutz’ stepdaughter.

“He was a very shy man, it was not necessarily in his nature to do what he did. But he saw the misery of the Jews and he thought he had to help.”