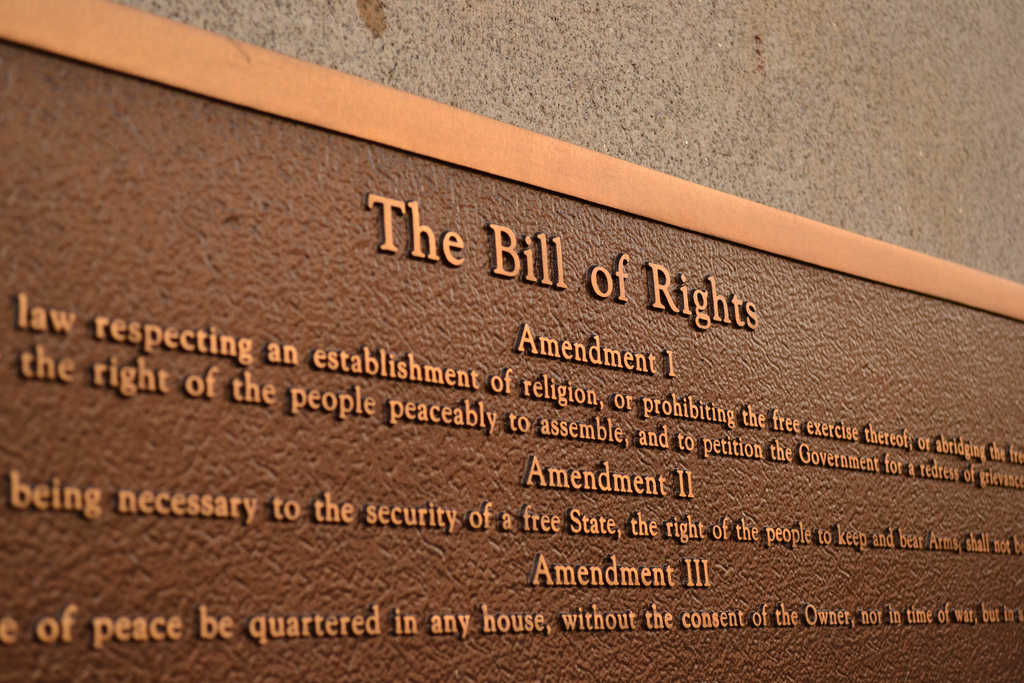

Wind back 226 years and you come to a sacred date in American history: December 15, 1791. It was on this day that Bill of Rights was ratified and enshrined in the nation’s history. Perhaps, then, now is a good time to reflect on the state of religious freedom in the United States, and to ask ourselves the question: are we committed the protection of our constitutional rights?

The Charters of Freedom contains the United States Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights. The very first words of that charter document declare: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.”

Today, we hear a lot about “religious tolerance” and the protection of a “tolerant” society. Whilst this is important, these founding documents were getting at something much more muscular when it comes to the preservation of religious liberty.

As First Liberty Institute’s Michael Berry pointed out at The Daily Signal:

“Mere “toleration” of “private” religious conduct was precisely what James Madison, a primary author of the Bill of Rights, was careful to avoid. He favored the protection of robust freedom.”

For Madison, “tolerance” was not nearly enough when it came to the fundamental right to practice one’s religion in peace:

“Madison recoiled at the notion that exercise of religion was a gift from government to be merely “tolerated.” He saw it rather as a hallmark of a free society—an unalienable right endowed by a creator—that exists independent of government,” adds Berry.

After observing many years of religious persecution, Madison sought to end the whole idea of religious tolerance, and ushered in a much more sturdy take on the First Amendment: “The civil rights of none shall be abridged on account of religious belief or worship … nor shall the full and equal rights of conscience be in any manner, or on any pretext infringed,” he wrote.

So, personal conscience on account of one’s religious beliefs was brought under the umbrella of constitutional protection. This makes for fascinating reading when you consider the landmark religious liberty cases before the Supreme Court today.

Is one’s conscience, on the basis of one’s religious convictions, allowed to be expressed in the public sphere? Or are we merely tolerating the established practice of religion as a private matter that must never influence the decisions we take in our public or professional lives?

As we know, the final version of the First Amendment redacted the term “conscience” and reads as follows:

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

Berry brilliantly summarizes Madison’s constitutional influence:

“The states ratified a revised version of Madison’s text as the First Amendment to our Constitution, and the first of our Bill of Rights. His gift to the fledgling republic was to reject the notion that individual rights, and pre-eminently religious liberty, were mere tokens bestowed by a beneficent state, replacing that view with the remarkable notion that these rights are inseparable from our humanity.

In other words, the right of every person to enjoy religious liberty doesn’t exist just because the government says it does—and any government that attempts to dictate otherwise risks illegitimacy.”

So, perhaps it is time to seriously question the state in which we find ourselves when it comes to the protection of religious freedoms in America today. Is it it about time we reassessed the civic outworkings of tolerance, conscience and the expression of a faith-based conviction in public life?

What do you think?

(H/T: The Daily Signal)