Intended to share the good news of the freedom that can be found only in Jesus, the Bible was at one time in history used for the exact opposite purpose: it was once used to enslave.

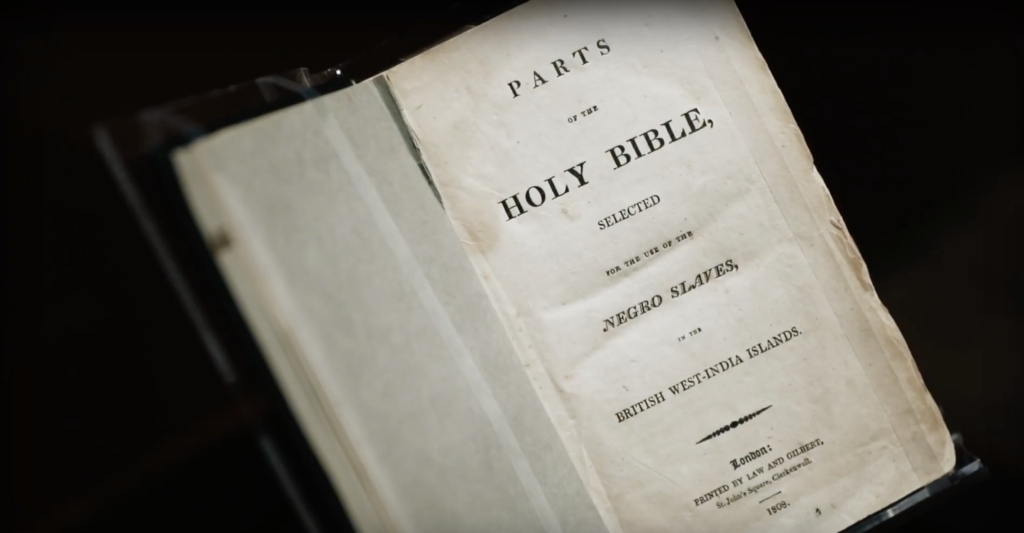

The so-called “Slave Bible” is currently on display at the Museum of the Bible in Washington, D.C. On the outside, it looks like any other copy of the Scriptures, but the pages within tell an entirely different story.

The “Slave Bible” was selectively edited to remove roughly 90 percent of the Old Testament and 50 percent of the New Testament, according to Anthony Schmidt, a curator at the Museum of the Bible.

What was taken out?

The Old Testament book of Exodus was taken out the “Slave Bible” because the Hebrew text tells the story of Moses demanding Pharaoh free the Israelites from captivity in Egypt.

Jeremiah was also removed from the edited version of the Bible because of verses like the one found in the 22nd chapter of the Old Testament book: “Woe to him who builds his palace by unrighteousness, his upper rooms by injustice, making his own people work for nothing, not paying them for their labor.”

The “Slave Bible” was also stripped of the New Testament book of Galatians. In it, the apostle Paul declares, “There is neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free, nor is there male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus.”

What remained in the book, though, were passages like Ephesians 6:5, which reads, “Slaves, obey your earthly masters with respect and fear, and with sincerity of heart, just as you would obey Christ.”

Why was it edited?

The Bible’s formal name was “Parts of the Holy Bible Selected for the Use of the Negro Slaves in the British West-India Islands.” It was published in 1807 in London.

Schmidt said the museum concluded the controversial text was likely produced by a missionary organization known as “The Society for the Conversion of the Negro Slaves,” one of many such societies that popped up in the early 1800s.

Those missionaries, the curator explained, believed the edited Scriptures “would improve the lives of enslaved Africans both materially and spiritually.”

“This book,” Schmidt said, “is aimed at justifying and reinforcing the slave system. But at the same time, it was used to help teach Africans how to read, for example, and to somehow educate them in the classroom.”

While many of the missionaries, he argued, were abolitionists, they were uncomfortable — largely because of their society’s cultural and political makeup — with the idea of emancipation.