I have to wonder: What would Frederick Douglass think of us?

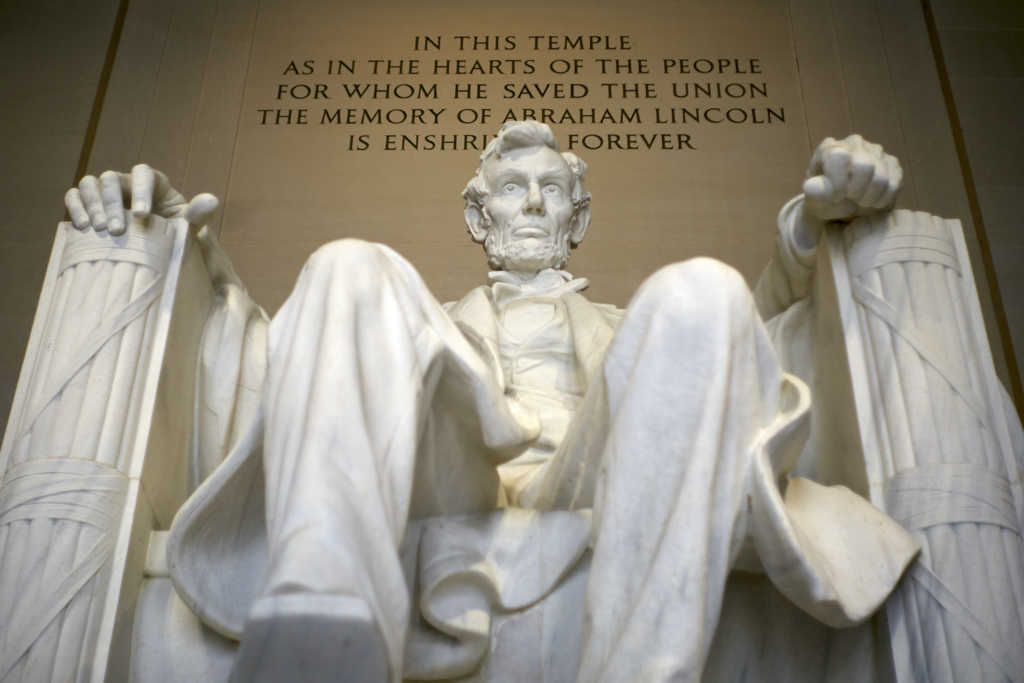

On Tuesday, a group of angry protesters gathered around a statue the great abolitionist — himself a formerly enslaved man — dedicated on April 14, 1876, 11 years after the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln, who signed the Emancipation Proclamation, freeing all enslaved peoples.

Standing in the D.C. plaza surrounded by prestigious members of the U.S. Congress, members of the U.S. Supreme Court, and President Ulysses S. Grant, Douglass delivered a stirring address in celebration of the what later became known as the Emancipation Memorial.

Douglass, more than the memorial itself, was moved by the peacefulness of the celebration in the nation’s capital. He was overcome to see people with white and brown skin coming together to celebrate not only the unveiling of the statue, but the freedom it represented.

Here’s a particularly poignant portion of Douglass’ dedication:

I cannot forget that no such demonstration would have been tolerated here 20 years ago. The spirit of slavery and barbarism, which still lingers to blight and destroy in some dark and distant parts of our country, would have made our assembling here the signal and excuse for opening upon us all the flood gates of wrath and violence. That we are here in peace today is a compliment and a credit to American civilization, and a prophecy of still greater national enlightenment and progress in the future.

I refer to the past not in malice, for this is no day for malice; but simply to place more distinctly in front the gratifying and glorious change which has come both to our white fellow citizens and ourselves, and to congratulate all upon the contrast between now and then; the new dispensation of freedom with its thousand blessings to both races, and the old dispensation of slavery with its ten thousand evils to both races — white and black. In view, then, of the past, the present, and the future, with the long and dark history of our bondage behind us, and with liberty, progress, and enlightenment before us, I again congratulate you upon this auspicious day and hour.

It would certainly grieve Douglass today to see the group of progressive protesters vowing to destroy and tear down that very memorial, which was paid for by freed slaves, as well as its replica in Boston.

To Douglass, the Emancipation Memorial’s placement in the heart of Washington, D.C., was itself a form of peaceful protest — a beacon of freedom and a reminder of the equal place black Americans ought to have in the country:

We are here in the District of Columbia, here in the city of Washington, the most luminous point of American territory; a city recently transformed and made beautiful in its body and in its spirit; we are here in the place where the ablest and best men of the country are sent to devise the policy, enact the laws, and shape the destiny of the Republic; we are here, with the stately pillars and majestic dome of the Capitol of the nation looking down upon us.

We are here, with the broad earth freshly adorned with the foliage and flowers of spring for our church, and all races, colors, and conditions of men for our congregation — in a word, we are here to express, as best we may, by appropriate forms and ceremonies, our grateful sense of the vast, high, and pre-eminent services rendered to ourselves, to our race, to our country, and to the whole world by Abraham Lincoln.

If you’re still not sure how Douglass might feel about the effort now to tear down the Emancipation Memorial, look no further than this chilling and powerful portion of his dedication in 1876:

Let it be known everywhere … [that] we, the colored people, newly emancipated and rejoicing in our blood-bought freedom, near the close of the first century in the life of this Republic, have now and here unveiled, set apart, and dedicated a monument of enduring granite and bronze, in every line, feature, and figure of which the men of this generation may read, and those of after-coming generations may read, something of the exalted character and great works of Abraham Lincoln, the first martyr President of the United States.

Douglass knew then at the end of the 19th century that memorial wasn’t a beacon just for his day, but one for generations to come — a beacon for the United States in 2020, when we are bursting at the seams with division and vitriol.

The famed abolitionist knew Lincoln wasn’t perfect. In fact, Douglass referred to him as “pre-eminently the white man’s president,” but added: “While Abraham Lincoln saved for you a country, he delivered us from a bondage, according to [Thomas] Jefferson, one hour of which was worse than ages of the oppression your fathers rose in rebellion to oppose.”

And to those who are so confused to believe the statue — which depicts Lincoln standing with his arm outstretched as a freed slave on one knee lifts his head up — depicts servitude, look again.

The memorial is rich with meaning and shouts the message of freedom.

As one woman explained to WJLA-TV: “That man is not kneeling with two knees with his head bowed. He is in the act of getting up. And his head is up — not bowed — because he’s looking forward to a future of freedom. People have said, ‘Well, he’s chained to Mr. Lincoln.’ With a closer look, you’ll see that, while there’s a shackle on his right hand, he’s holding the end of a broken chain, which means he has taken to his freedom. He now realizes that he’s free.”

“So I say leave it,” she continued. “Let it stand.”