With a unanimous vote, the Boston Art Commission voted Tuesday to get rid of the Emancipation Memorial commemorating President Abraham Lincoln’s signing of the proclamation that ended slavery in America.

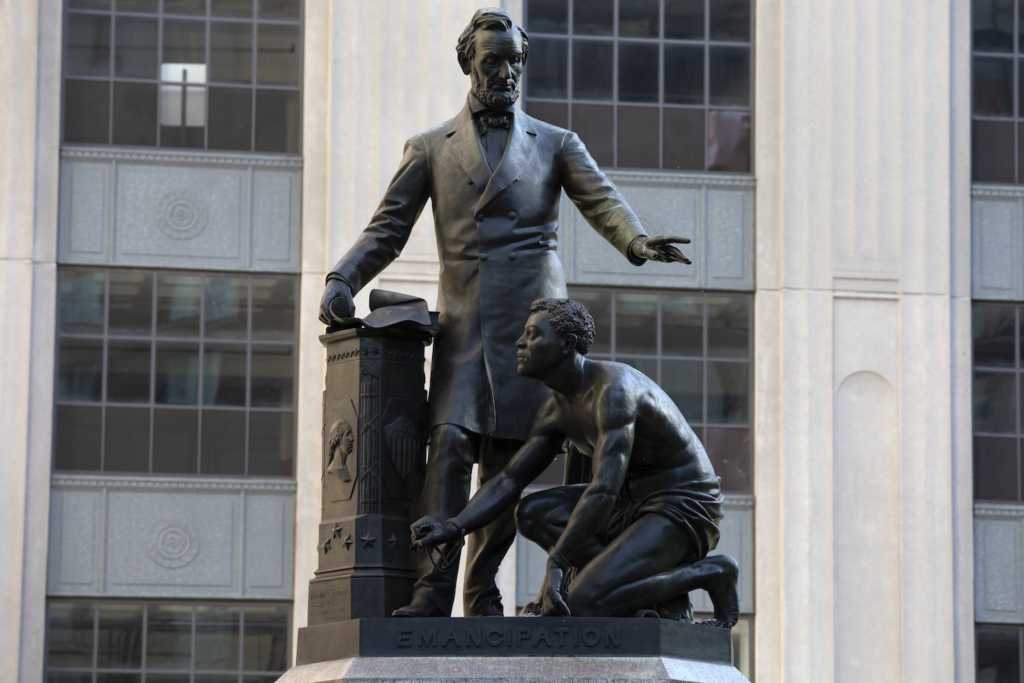

The statue, first erected in 1879, is a replica of the monument in Washington, D.C., that depicts Lincoln standing with a freed slave in the process of standing up as shackles fall from his arms. The inscription at the base of the statue, which was paid for by freed slaves and dedicated by the beloved abolitionist Frederick Douglass, reads: “A race set free and a country at peace. Lincoln rests from his labors.”

Boston Mayor Marty Walsh (D) issued a statement in support of the decision to remove the Boston-based replica of the Emancipation Memorial, which follows weeks of peaceful Black Lives Matter protests and violent riots that led to the destruction of public and private properties in cities across the country.

“As we continue our work to make Boston a more equitable and just city,” he said, “it’s important that we look at the stories being told by the public art in all of our neighborhoods.”

He went on to say:

After engaging in a public process, it’s clear that residents and visitors to Boston have been uncomfortable with this statue and its reductive representation of the black man’s role in the abolitionist movement. I fully support the Boston Art Commission’s decision for removal and thank them for their work.

The petition calling for the statue of the Great Emancipator to be taken down garnered more than 12,000 signatures.

“I’ve been watching this man on his knees since I was a kid,” wrote the petition’s creator, Tory Bullock. “It’s supposed to represent freedom but instead represents us still beneath someone else. I would always ask myself, ‘If he’s free, why is he still on his knees?’ No kid should have to ask themselves that question anymore.”

But, as the woman in the video above explains of the original memorial in Washington, D.C., that is not at all what the statue depicts.

“That man is not kneeling with two knees with his head bowed,” she said. “He is in the act of getting up. And his head is up — not bowed — because he’s looking forward to a future of freedom. People have said, ‘Well, he’s chained to Mr. Lincoln.’ With a closer look, you’ll see that, while there’s a shackle on his right hand, he’s holding the end of a broken chain, which means he has taken to his freedom. He now realizes that he’s free.”

“So I say leave it,” the woman added. “Let it stand.”

During his dedication of the original statue on April 14, 1876 — 11 years after Lincoln’s assassination — Douglass delivered a powerful dedication in front of then-President Ulysses S. Grant, members of the U.S. Congress as well as justices of the U.S. Supreme Court.

“Let it be known everywhere,” he declared, “[that] we, the colored people, newly emancipated and rejoicing in our blood-bought freedom, near the close of the first century in the life of this Republic, have now and here unveiled, set apart, and dedicated a monument of enduring granite and bronze, in every line, feature, and figure of which the men of this generation may read, and those of after-coming generations may read, something of the exalted character and great works of Abraham Lincoln, the first martyr president of the United States.”